Book Review: Crash! From Senna To Earnhardt – How The Hans Helped Save Racing

Racing safety equipment is incredibly complex. Figuring out materials, weight, breathability, rating, fit, color preference, FIA vs. SFI, can it be re-certified, what type of car will this equipment be used in, will it have a roof, et cetera… it takes a lot of effort and knowledge. There is an incredible amount of information to factor in to one’s individual needs, to not only meet their sanctioning body’s safety requirements, but also their own personal requirements.

Though, not terribly long ago, both sanctioning bodies and individuals didn’t have much in terms of safety requirements.

In fact, considering how extensive regulations are in our modern era, it’s truly frightening how minimal requirements were even just thirty years ago. Fifty years ago is even harder to fathom.

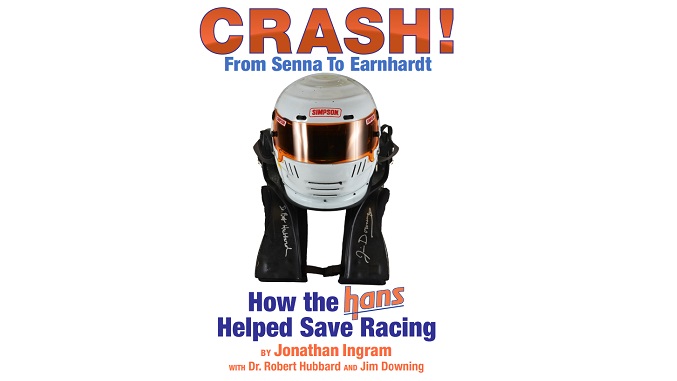

Jonathan Ingram’s book Crash! From Senna To Earnhardt – How the Hans Helped Save Racing gives readers a thorough, well-documented look at racing safety over the past century, and also goes deep into the psychological and sociological topics behind it. Its centerpiece is quite clear: the development of the Hans device and its impact on racing safety, which is truly monumental, not just because it dropped the fatality rate, but also because it genuinely saved racing at all levels. If you’re a history nerd like us, you’ll really appreciate the detail that Ingram goes into to prove this point.

The Hans’ humble beginnings as a device conceived by American racing legend and proud Georgian Jim Downing and his brother-in-law, biomechanical engineer Dr. Bob Hubbard, is fascinating, and a testament to good ol’ fashion American ingenuity. Anything highlighting American ingenuity always piques our interest! A good amount of light is shed on Hubbard and Downing themselves, as well as several other key individuals, institutions, and companies who were crucial in the device’s creation. Shout-out to the grand state of Michigan and its public university system.

The key injury that is presented, which the Hans was developed to solve, is the basal skull fracture. Ingram provides a good number of frightening examples of tragedy where this almost-always-fatal injury has occurred in professional racing. Downing himself narrowly avoided this fate, but only just barely: his IMSA GTU Mazda RX-7 collected a wall in reverse at Mosport in 1980. Had he impacted the wall head-on, history would’ve looked significantly different.

Ingram utilizes a good number of pages early in the book to discuss the historical machismo behind motorsports. At times, it was a significant hindrance on the progression of safety technology. Incredible danger was an aspect that was celebrated often, and when it wasn’t, it was just accepted (which is mindblowing by today's standards).

From early 20th-century board racing, to early the early years of IndyCar and Formula 1, a lot of catastrophic loss occurred on track before any form of progress was made. The progression from incredibly dangerous with minimal protection, to still incredibly dangerous though with what we’d call minimal protection by today’s standards, had a very, very mild arc. Ingram makes sure to discuss the press’ reaction to racing’s danger and the horrific deaths caused by it, and in-turn society’s take, depending upon which form of racing or era it takes place during.

The deaths of Ayrton Senna and Dale Earnhardt are highlighted for many aspects in the book, including the press’ reaction. Le sport noir or "the black sport" was coined by the French press after Senna’s death, and as Ingram details, this term isn’t quite lifted until real safety is implemented in the early 2000s.

In between the timeline of tragic losses, there were some voices of reason, which Ingram presents and goes into detail about quite well. Notably, American legend Phil Hill (whose name blesses one of the scariest sections of track on the West Coast at Buttonwillow) and Scotsman Jackie Stewart; two of our favorite drivers of all time. They both in their own way and era were vocal about it being preposterous to have so little protection, and not wanting to be in a wheelchair by middle age. Stewart’s own horrific scenario went down at Spa in 1966, where fellow competitors Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant removed him from his crashed BRM, which had turned into a bathtub of gasoline. Stewart went on to lead a safety crusade that saw the invention of Nomex, eventually better harnesses, and some significant changes to cockpit design.

Though something to prevent basal skull fractures still hadn’t come along yet. This was the nearly-always-fatal injury that the Hans was designed to prevent, and its cause was any high speed impact. It wasn’t until the early 80s that such development began, championed by Hubbard and Downing, and once again Ingram covers quite thoroughly. The timeline between a large, gel-coated monstrosity to slim, carbon fiber, mandated piece of equipment is very long and very, very expensive. But the timeline is presented well, and its great to read up on how the Hans not only became a necessity for high-level pro racing, but also trickled down to become available to weekend club racers.

Ingram does touch on the Hans’ skeptics, too. There weren’t just skeptics who disliked the inconvenience of the Hans, there were some who said it would cause harm in its own way. We don’t want to give away too much from this chapter, but if there’s ever a chuckle-worthy moment within its pages, this might be it. It also must be said that sanctioning bodies had some other remedies in mind, especially after Senna's death, that seem ridiculous by today's standards.

Throughout the entire book, racer lingo is absolutely spot-on. As with any sport, there’s a certain dialect we learn as we dive deeper into motorsports, either by keeping up with it in the media, watching from the stands, or getting behind the wheel ourselves. Maybe we’re biased, but the reference guides for racer lingo might be substantially larger than any other sport. Ingram keeps the reader tuned-in quite well with describing events that go down on track (such as Jackie Stewart at Spa in 1966), race car engineering, safety engineering, and racing culture, and does so as if you’re sitting in the pit conversing with buddies after the track goes cold. The language is never dense, either; just an enjoyable book full of facts that flows well and encourages the reader to keep turning pages (especially if they're even mildy engineering-inclined, which is most likely 99% of racing enthusiasts).

We definitely recommend Crash! From Senna To Earnhardt – How the Hans Helped Save Racing to anyone who’s interested in the history of racing safety, how the Hans became what we know it as today, or really just the history of racing in general. There are so many moments highlighted within this book’s 172 pages, it’s a great starting point to learn more about CART, Formula 1 in the 1950s, the history of IMSA, NASCAR hall of famers, and more. A lot of detailed research was performed, and many, many major names in the industry had a hand in putting it together. It is quite apparent that Ingram is massively passionate about all things motorsports, and that he wants the world to know why the Hans is so crucial to its well-being.

Check out his website, jingrambooks.com, to pick up a copy for yourself! We wish Jonathan all the best with slingin’ copies to racers all over the world, and thank him for sending us a copy for this review.